Dry eye syndrome (DES) is a multifactorial ocular surface disease (OSD),1–3 the incidence of which is about 16 %,4–7 and is one of the most common reasons why people visit their ophthalmologist – approximately one in three patients seek treatment from a specialist.8

Many cases of dry eye are associated with other disorders such as meibomian gland disease (MGD), conjunctivochalasis or even allergy. Recently, the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS)1 and the Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Workshop9 redefined these conditions. It is relevant and somewhat novel that in both definitions, DES and MGD, inflammation appears as a major factor in the pathogenesis. This will be important in providing a more definitive approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Cataract or refractive surgery often aggravate the symptoms of DES,11 and there is evidence to show how these patients have poorer outcomes after surgery.11 In patients with DES undergoing laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) surgery, a worsening of symptoms or onset of discomfort in patients who were previously asymptomatic,12 or even a reduction of functional visual acuity,13 have been described.

We also know that MGD is the most prevalent cause of evaporative dry eye.14 Pre-existing MGD can double a patient’s risk of developing DES,15 especially after ocular surgery, which can negatively affect outcomes.15–19

For these reasons it is important for ophthalmologists to consider DES and OSD whenever they approach surgical patients in order to identify and treat these conditions pre-operatively and thus optimise surgical outcomes.

Diagnosis

Traditional tests to diagnose OSD provide limited practical information.20 Fortunately this has changed recently and the combination of clinical history, subjective symptoms and, especially, data provided by new technologies, help us with a given diagnosis. We emphasise the value of the patient’s clinical history. The presence of other diseases, ocular and systemic, as well as certain medications are fundamental factors in the onset and course of the disease.

According to the DEWS report, risk factors for dry eye to be taken in account before surgery include:

- Increasing age;

- Female gender, especially women who are post-menopausal and taking oestrogen;

- Deficiencies of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and vitamin A;

- Oral medications, including antihistamines, betablockers, tricyclic antidepressants and diuretics;

- Topical medications, especially those containing preservatives, such as benzalkonium chloride;

- Systemic diseases, namely autoimmune disease, including Sjögren syndrome and diabetes;

- Ocular surgery, in particular, laser vision correction and cataract surgery, especially when limbal relaxing incisions are used; and

- Stem-cell transplantation, especially when graft versus host disease occurs.

To achieve a complete approach to OSD, diagnosis should include a standardised questionnaire, such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI); McMonnies; Schein; Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ); Ocular Comfort Index (OCI); or the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness (SPEED), followed by non-invasive objective testing. New technologies include:

- New corneal topography: measure tear break-up time and tear meniscus height objectively (Keratograph, Oculus).

- New optical coherence tomography (Fourier domain OCT) objectively quantifies the tear meniscus height and volume.

- Dynamic Wavefront aberrometry (the Oral Controlled Absorption System [OCAS]) measures the inter-blink change in higher-order aberrations and, thus, provides a quantitative assessment of tear-film quality and stability.

- Corneal interferometry measures the lipid layer of the tear fllm providing useful information on the functional status of Meibomian gland.

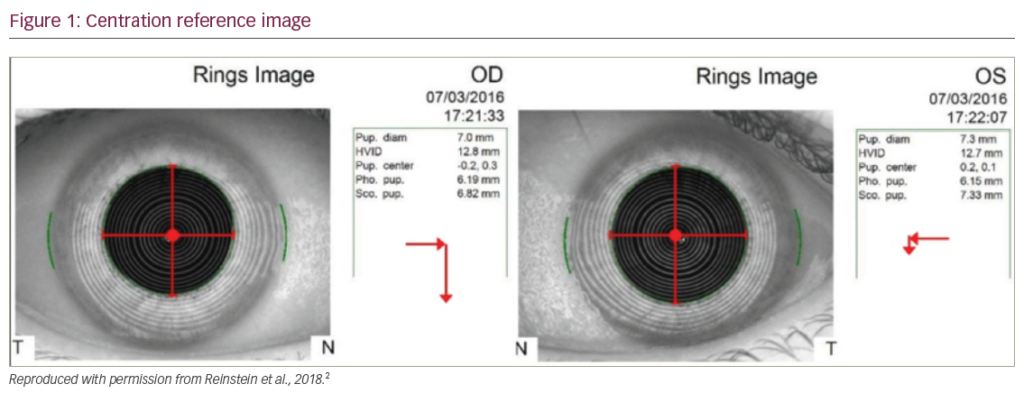

- Meibography can visualise meibomian glands (see Figure 1) using new topography measures with infrared light and high-resolution images (Keratograph 5M, Oculus, Arlington, WA, US).

- Confocal microscopy can show inflammation at the cellular level. Researchers have used it to view the ductal changes that occur in MGD.21

- Tear Osmolarity. Tear hyperosmolarity and the resultant inflammation is a main mechanism in the OSD cycle. Studies have shown a strong, linear correlation between osmolarity and dry eye severity, as well as tight correlation with symptoms.22 Available on the market is a non-invasive, quick, simple, point-of-care tool for measuring tear osmolarity (TearLab Osmolarity, San Diego, CA, US)

Similarly, a simple-to-use, non-invasive, point-of-care test (InflammaDry Detector, RPS, Inc., Sarasota, FL, US) will be available to measure elevations in tear matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels, one of the most important inflammatory mediators that are increased in the tears of patients with OSD.

Figure 1: Meibography (Oculus Keratograph™)

Treatment

As discussed above, DES and MGD, and also conjuntivochalasia, are frequently present in patients pre-operatively. These conditions are often overlooked, because the symptoms or signs are mild and surgeons do not consider their presence. Nonetheless, they may disturb the tear film, which could negatively affect outcomes and the patient’s recovery.23,24

In this article, a practical guide is described to prepare patients before surgery and treatment recommendations after surgery.

Figure 2: Intraductal Meibomian Gland Probing

Pre-operative Treatment

In patients with DES and MGD, four actions as first-line treatment are recommended: local heat, mechanical massage, cleaning of the eyelids and topical antibiotics (azithromycin). In some cases patients can benefit from adjunctive therapy with anti-inflammatory drugs, especially topical cyclosporine (Restasis, Allergan, Inc.) that has been shown to have efficacy for both blepharitis and aqueous deficiency dry eye.25–27

In some cases with difficult MGD, intraductal meibomian gland probing (see Figure 2) is necessary to open blocked meibomian glands to improve the quality of the secretions and thus help to stabilise the tear film. In many cases, punctal plugs are a helpful complement to prepare these patients before surgery.

Demodex folliculorum is another condition to take in account. Little is known about the extent to which this microorganism can influence the pathophysiology of DGM as a vector for bacterial colonisation. Some authors recommend using washes with tea tree oil 50 %, and provide this treatment in the office because of the potential toxicity of this substance to the cornea.

Sex hormones (androgens) are known to play an important role in regulating the function of the meibomian glands, but no studies exist that demonstrate therapeutic benefit in the DGM.

When conjunctivochalasis is present and patients are symptomatic, it is necessary to evaluate two alternatives: medical treatment with lubricants or the need for surgery (to remove the folds of conjunctiva and especially fix the conjunctiva to the sclera with bioadhesive).

Post-operative Treatment

Quick identification of the problem is crucial. In most of our patients we start post-operative treatment OSD with preservative-free artificial tears during the day and artificial tear gels or lubricants at bedtime. In symptomatic patients we recommend topical cyclosporine or low-dose dexamethasone 0.01 %. and punctual plugs.

When MGD is present we recommend topical azithromycin, either alone or in combination with oral doxycycline, if tolerated. I also instruct these patients to use warm compresses and massage their eyelids. An artificial tear containing a lipid component can help to reduce evaporative tear loss in these patients.

Oral omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to be an effective complement in post-operative OSD. The omega-3 fatty acids improve the production of anti-inflammatory prostaglandins and the lipid component of the meibomian gland secretions28–30 helping to stabilise the tear film.

Patients who remain symptomatic despite aggressive therapy may benefit from preservative-free artificial tears. The use of autologous serum and moisture-chamber goggles are additional options for patients with severe DES.

Conclusion

Identifying and treating DES pre-operatively can help to avoid post-operative surprises. The early identification and treatment of postoperative DES will hasten patients’ recovery, prevent their frustration and enhance surgical outcomes.

Questionnaire

We conducted a questionnaire with 20 surgeons in cataract and refractive surgery, to enquire about the importance given to the presence of OSDs in patients having ocular surgery. We sought to get their opinion on whether they performed pre-treatment, if new technologies were employed and if they manage these concerns themselves or prefer to refer the patient to a specialist in OSD. The responses were predictable up to a point. All gave importance to the presence of OSD and their treatment pre- and post-surgery, but not all considered important new technologies; some do not treat the patients themselves, but would rather refer to another specialist. The final question looked at how surgeons believed ocular surface disorders affected the surgical outcomes. The mean score was 7.2 (scale given in question 5), which is a good score but we believe it is necessary to further raise awareness of the role that OSD plays in the success of cataract and refractive surgery among surgeons.

- Do you make some type of pre-operative study to rule out OSD before cataract or refractive surgery? 20/20: YES

- Do you consider the use of new technologies such as Dynamic Wavefront (sequential aberrometry between blinks), meibography, interferometry to study the tear film or confocal microscopy to study corneal inflammation necessary to analyse ocular surface before surgery? 12/20: YES

- If ocular surface disorders exist pre-operatively, do you use specific treatment before surgery? 20/20: YES

- As a cataract and refractive surgeon, do you manage the pre- and post-operative treatment yourself or do you prefer to refer to a specialist in OSD? 14/20: treat themselves and six surgeons refer patients to a specialist in OSDs.

- How do you think the presence of ocular surface disorders affect the outcomes of surgery, on a scale from 0 (no importance) to 10 (extremely important)? Mean: 7.2