Inherited retinal dystrophies (IRD) are genetic disorders characterised by variable, albeit progressive degeneration of the retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choriocapillaris (CC).1,2 Prevalence varies in different countries, affecting approximately 1 in 4,000 individuals, with symptoms including poor peripheral or night vision, metamorphopsias, reduced central vision or blindness.1,3 Their pattern of inheritance may be autosomal recessive (e.g. Stargardt disease), autosomal dominant (e.g. Best disease), X-linked (juvenile retinoschisis and choroideremia) or mixed (e.g. retinitis pigmentosa, with all its phenotypes). Chorioretinal dystrophies also present a high degree of clinical, pathophysiological and histological findings, making their diagnosis and management occasionally challenging.4–9 In this regard, the use of multimodal imaging and genetic characterisation are increasingly recognised as fundamental instruments in the assessment of patients affected by these disorders.10–13

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) angiography (OCT-A) represents a functional extension of OCT technology, employing motion contrast from blood flow rather than simple reflectance intensity to acquire, in a few seconds, high-resolution information about ocular vessels.14 Although fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography are still considered the gold standards for the assessment of all the retinal vascular diseases, OCT-A is progressively gaining rapid and positive consensus among ophthalmologists as a valid alternative or integrative technique to the previously mentioned angiographic modalities.15,16

For these reasons, OCT-A is one of the most recent and utilised tools to investigate the presence and the extent of the vascular alterations in IRD.17–18 Its advantages include the possibility to analyse the vascular profile of these patients in a non-invasive (dye-less) and rapid (few seconds) manner, devoid of adverse effects. Moreover, OCT-A allows a depth-resolved study of retinal vasculature in patients who would not be the best candidates for other angiographic examinations, including those with renal disorders, pregnant women and those with hypersensitivity reactions. Even though vascular impairment has been described in several dystrophies, no specific review has thoroughly analysed the different vascular involvement in the main chorioretinal dystrophies or focused on their clinical implications and future perspectives.

In recent years, numerous OCT-A studies have focused on the extent and evolution of vascular impairment in IRD, evaluating their relationships with the fundus findings, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) outcome and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT). The most common parameters included vessel density (expressed as percentages, %) and foveal avascular zone area (FAZ, expressed as mm2).19–33

The primary outcome of this article is to review the main vascular alterations occurring in IRD described in literature. Secondary outcomes include the discussion of the potential clinical and pathophysiological implications of such vascular impairment.

Retinitis pigmentosa

The diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) includes a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of IRD, principally characterised by the progressive dysfunction of rod photoreceptors and followed by secondary degeneration of cones and retinal pigment epithelium.34

Of note, the appearance of the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) and deep capillary plexus (DCP) seems qualitatively altered, this finding being especially marked in the temporal sector of these patients.19 These results have indeed been confirmed by some quantitative studies, disclosing a general rarefaction of the retinal plexuses when compared with control subjects, both in the foveal and para-foveal areas.19–21 Interestingly, no study has identified significant damages in the CC plexus of these patients. With regard to the FAZ area, a meaningful enlargement was exclusively described at the level of the DCP, especially in the presence of visual acuity deterioration.19,20 Figure 1 shows the typical vascular changes of patients with RP.

Stargardt disease

Stargardt disease (STGD) is considered to be the most frequent recessive macular dystrophy, resulting from the accumulation of lipofuscin in the RPE and leading to secondary photoreceptor dysfunction.35,36 Patients are generally homozygous for ABCA4 gene mutations.

From a qualitative point of view, signs of vascular rarefaction are particularly evident in the temporal area, both in the SCP and the DCP; moreover, the lipofuscin-filled flecks seem to exert a clear masking effect on the underlying CC layer.22 A few quantitative analyses have supported this reduced vessel density in both SCP and DCP when compared to controls, whereas vessel density does not appear to be affected in the CC of patients with STGD.22–4 Nevertheless, in the subgroup of patients with SD-OCT-documented macular atrophy, a marked rarefaction is also detected in the CC.22,23 An enlargement of the FAZ area is instead appreciable at the level of SCP.22 Figure 2 illustrates the vascular damage occurring in eyes with Stargardt disease.

Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy

Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy (AOFVD) is a form of pattern dystrophy characterised by bilateral, yellowish sub-foveal deposits (one-third to one disc in diameter) and by a slow clinical progression.37 Although associated with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance (e.g. peripherin and RDS genes), a distinct genetic mutation is not detected in most cases.38

On OCT-A, a well-defined vascular rarefaction is especially identifiable at the SCP and CC.25–7 Although the results from the DCP vascularity appear controversial,25,27 FAZ area seems instead to be significantly enlarged in this vascular plexus. Figure 3 shows the vascular alterations occurring in AOFVD.

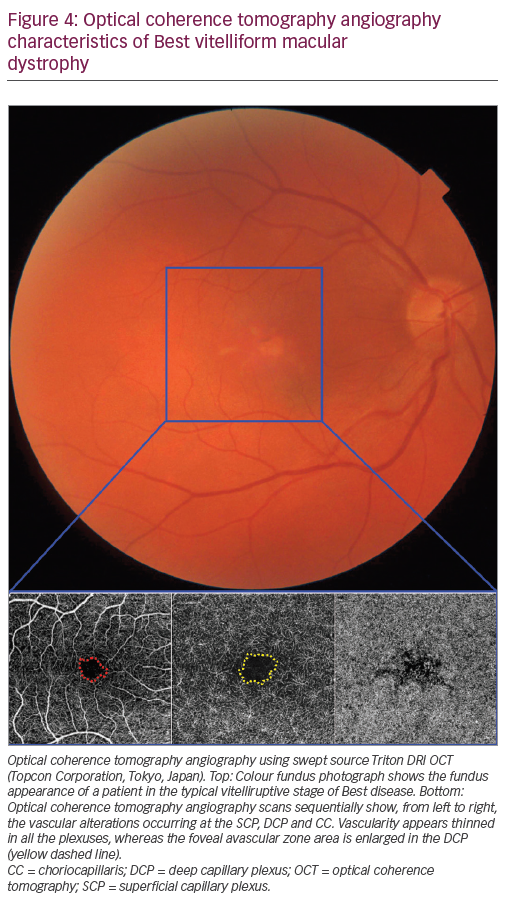

Best vitelliform macular dystrophy

Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD) is a dominantly-inherited macular dystrophy, characterised by a typical egg yolk-like lesion in the early stages of the disease.39 BEST1 is the most commonly mutated gene in this dystrophy, which, however, shows high genetic and phenotypic variability.6

A marked rarefaction can be qualitatively perceived in all the vascular layers, particularly in patients with an advanced disease; in addition, the features of choroidal neovascularisation have been reported by several groups, reaching an outstanding 36% prevalence in the largest study currently available.28,29 Despite a clear masking effect exerted by the vitelliform material on the underlying CC, reduced vascular density can be identified in all the vascular plexuses of patients with BVMD, with an enlargement of the FAZ area occurring at the DCP.29 In addition, the stratification of patients according to Gass’ classic five stages revealed that a significant rarefaction particularly accompanies the stages following the vitelliform material disruption (stages three, four and five).29 Figure 4 shows the typical vascular changes of Best disease.

Choroideremia

Choroideremia (CHM) is a progressive form of retinal degeneration affecting the RPE, the choroid and the outer retina. Patients typically complain about nyctalopia and decreased peripheral vision from a young age, reaching legal blindness around the third to fourth decade.40

Although little information is currently available in the literature,30,31 our experience suggests that DCP results are dramatically altered in patients with CHM, whereas the SCP appears similar to controls. Moreover, the CC shows some vascular rarefaction exclusively limited to the area characterised by signs of chorioretinal degeneration, with the vascular alteration correlating with the extent of photoreceptor loss.31,32 Figure 5 illustrates the alterations occurring in CHM on OCT-A assessment.

X-linked juvenile retinoschisis

X-linked juvenile retinoschisis (XLJR) is a relatively common form

of retinal degeneration affecting young males and mainly manifests with splitting of the outer retinal layers in the macular region.41 Although no definitive proof is available, the effective use of dorzolamide in these patients highlights a vascular role in the pathogenesis of this disease.42

As suggested by a recently published case series,33 our experience points toward a meaningful capillary rarefaction detectable in the DCP of patients with XLJR, with this alteration being particularly marked in the foveal area. A remarkable FAZ area enlargement can be instead observed in the same vascular plexus. Table 1 summarises the vascular alterations described in these IRDs.

Discussion

Inherited retinal dystrophies comprise a broad group of genetic disorders with variable severity and different patterns of inheritance. Although the aetiology and the evolution of these diseases are quite different, all of them result in an irreversible loss of visual acuity and, as a consequence, a poor quality of life.3,4,6,8

Optical coherence tomography angiography is a relatively new imaging tool that allows a quick and non-invasive assessment of retinal and choroidal vascularisation. Since its introduction, OCT-A has been increasingly employed to describe the capillary alterations occurring in patients with various retinal disorders, opening the scene to new explanations of their pathogenesis. Moreover, in the last few years new approaches have been proposed in the field of IRD to improve their prognosis through early phenotypic characterisation, the prompt identification of treatable complications and the advancement of innovative therapies.43–47

Currently available data reveal that a marked reduction of the vessel density is noticeable from the earliest stages in most IRD; therefore the manifestation of these microvascular alterations might be implicated in the pathogenesis of these diseases as well. Even if the rarefaction observed by means of OCT-A was simply secondary to the damage occurring in the outer retina or RPE of these patients, the worsening functional outcomes or the boosting of the natural evolution of the disease are still imputable to the resulting vascular damage. Another clinically useful application of this technique regards the superior ability to identify macular choroidal neovascularisation in the presence of RPE-derived pigment exerting a clear masking effect above the underlying growing new vessels.

In addition, as in the last decade a rising attention has been progressively devoted to gene therapy approaches to treat these disorders (e.g. CHM and RP), OCT-A evaluation might add valuable information and act as a precise technique to pre-operatively assess the best sites for the injection of viral vectors or to indirectly evaluate the outcomes of this gene transfer from a vascular perspective.48,49

In conclusion, we acknowledge that there are several limitations to the currently available studies of IRD conducted by means of OCT-A, including the limited number of studies and patients present in the literature and the high variability found even within the different phenotypes of the same disease. Additional disputable aspects are characterised by segmentation or projection artefacts induced by the morphological alterations occurring in the retinal layers, making the microvascular assessment, to some extent, inaccurate.50 Therefore, further studies including larger cohorts and longer follow up are needed, along with a more detailed functional assessment, to better characterise the vascular profile of IRD and to further promote OCT-A as a well-established imaging tool in this field.