Introduction

Introduction

For almost 100 years, penetrating keratoplasty (PK) was the mainstay of therapy for patients with corneal endothelial disorders.1 That changed in 1998 with the introduction of posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK),2–4 later popularized in the United States as deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK).5–7 Selectivity was the new technique’s primary advantage. By replacing only the inner aspect of the cornea, many of the suture, astigmatism, and wound healing problems of PK disappeared. But while effective, DLEK ultimately proved too technically challenging for widespread adoption. So, the surgery was simplified, giving rise to Descemet stripping (automated) endothelial keratoplasty (DS(A)EK).8-11 And within five years, this modified technique became the global treatment of choice for corneal endothelial disorders. Still, few patients after DS(A)EK achieved best corrected visual acuities (BCVAs) exceeding 20/25. Probably, the graft’s layer of attached stroma was to blame, which thickened the cornea and seemed to undermine its optical performance.12-16

A stroma-less graft was the solution, arriving in 2006 in the form of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK).17-19 With a transplant composed solely of isolated Descemet membrane (and its endothelium), DMEK slashed graft thickness by 75 % compared to DS(A)EK, from 80 microns down to twenty. The results were dramatic: almost 80 % of patients reached ≥20/25 within six months after surgery.12,20,21

Recently, DMEK has been refined into a standardized ‘no-touch’ procedure, ready for the typical corneal surgeon in any clinical setting and at low cost.22 Compared to its predecessors (DSEK, DLEK, and their variations), DMEK provides better and faster visual recovery, usually with no additional complications. It is therefore poised to become the first-line option for corneal endothelial disorders worldwide.23

Preoperative Preparation of the DMEK Graft

Ideally, DMEK grafts are prepared in an eye bank, 1–2 weeks before surgery. There, the tissue undergoes several rounds of additional screening. Principally, this consists of evaluating the cell density and morphology of the donor endothelium. Grafts which appear abnormal under the microscope—those with scarce or atypical cells, suspicious for being dysfunctional—are discarded, raising the quality of the pool of tissue for transplant. Preparing the grafts weeks in advance also adds convenience: it saves time and safeguards against unexpected tissue shortage on the day of surgery.24 On the other hand, some ophthalmologists may prefer to create the grafts themselves, in the operating room, just before surgery.25 This is especially true in the United States, where few eye banks currently supply ready-to-use DMEK tissue. Each graft takes 30 minutes to prepare, and all the steps are the same, whether in the operating room or the eye bank.

The initially described DMEK graft harvesting technique consisted of stripping Descemet membrane from a corneo-scleral rim submerged in saline. This method was proven safe and reproducible, with <5 % tissue loss due to inadvertent tearing, and—surprisingly—no significant endothelial cell damage.24-28 Recently, the process was upgraded to a ‘no-touch’ procedure, making the preparation both safer and easier.29 As a bonus, the anterior portion of the corneas left over from creating the DMEK grafts (with the Descemet membrane stripped off, but otherwise intact) can be used for deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK). This added benefit applies only to DMEK, because DS(A)EK preparation – by incorporating some of the posterior stroma into the graft – mangles the corneal remains, leaving them less suitable for transplant.29-31

DMEK Surgical Technique

The standardized no-touch technique for DMEK was published by Dapena et al. in 2011.22 In brief, a 3.0 mm clear-cornea tunnel incision is made at the 12 o’clock position with a slit knife, followed by the creation of three side-ports using a surgical knife at 10:30, 1:30, and 7:30 (right eye) or 4:30 (left eye). Under air, the recipient’s Descemet membrane is first scored 360 degrees then stripped from the posterior stroma using a reversed Sinskey hook (Catalogue no 50.1971B, D.O.R.C. International, Zuidland, The Netherlands). The DMEK graft is thoroughly rinsed with balanced salt solution (BSS, Alcon Nederland BV, Gorinchem, The Netherlands) and stained twice with trypan blue 0.06 % (Catalogue no VBL.10S.USA, Vision blue™ ; D.O.R.C. International) to enhance its visibility in the recipient anterior chamber. Already curled into a roll due to the inherent elastic properties of the membrane itself, the graft may be nudged into a ‘double roll’ configuration by applying a flow of BSS directly across its surface.22

After staining, the DMEK double-roll is sucked into a custom-made glass pipette (D.O.R.C. International), then injected into the recipient anterior chamber through the 12 o’clock incision ‘hinge down’ so that the double roll faces upward. Once the graft has been inserted, its orientation can be checked (and verified as properly ‘hinge down’) through the use of the Moutsouris sign, whereby the tip of a 30G cannula, positioned atop the edge of the graft, will turn blue if it is embraced by an upward facing roll. If the tip does not turn blue, then the roll must be facing down, and therefore the graft is upside down, which can be corrected by gently flushing it within the anterior chamber (see Figure 1).22

With the graft properly oriented, it may be unfolded by injecting a small air bubble in between the double rolls, then stroking the surface of the cornea to move the bubble and spread out the graft (Dapena technique). Once it has been fully unfolded, the graft is fixed against the recipient posterior stroma by completely filling the anterior chamber with air for a period of one hour. Afterwards, the air fill is reduced to 30–50 %, and the patient is instructed to remain supine for 24 hours.22 Variations on DMEK surgery do exist, however, with DMAEK and DMEK-S being the most prominent examples.32-35 These differ from regular DMEK in that a stromal rim is left attached to the periphery of the graft during preparation, which allows grasping and a ‘drag-and-drop’ insertion method. Otherwise, the surgery is the same.

Results

Visual Acuity

After DMEK, 77 % of eyes may achieve a BCVA ≥20/25 at six months, with 50 % ≥20/20. Visual rehabilitation is frequently fast, not uncommonly rebounding to 20/20 within the first post-operative week, and with most patients reaching their final BCVA within 1–3 months.19,22,23,26 (DMAEK and DMEK-S, likewise, seem to offer similarly good results.35,36 ) No other form of corneal transplantation offers comparable outcomes. After PK, less than 50 % of patients achieve visions of ≥20/40, and then only at one year.37 Following DS(A)EK, the average vision at six months is 20/40, rarely reaching 20/25 or better.12-16 Tellingly, in those patients with poor vision after DSEK, many dramatically improve with a re-operation to replace their DSEK graft with a DMEK (see Figure 2).38 Moreover, in people with one eye operated with each technique – one eye DSAEK, one eye DMEK – overwhelmingly, they prefer the vision in their DMEK eye.39

Refractive Change and Stability

After DMEK, both the spherical equivalent (SE) and cylindrical error are frequently within 1.0D of the pre-operative refractive error. Pachymetric and refractive data show that the transplanted cornea stabilizes three months after surgery, at which point new glasses may be prescribed. Until then, most patients are able to wear their current prescription.23

Endothelial Cell Density

Most DMEK grafts show a ±30 % reduction in cell density six months after surgery. Thereafter, cell density falls at a steady, predictable rate—at about 10 % per year.26,40–42 Interestingly, the transition to an entirely no-touch technique has had no effect on the measured ‘cell-loss’ after DMEK.22 The strong implication is that mechanical damage during transplantation cannot be the cause. More likely, the rapid fall in cell density after surgery reflects a decline in cellular concentration—not number—as the endothelial cells migrate out from the graft onto peripheral parts of the patient’s posterior stroma. Cell density measurements after DS(A)EK are almost identical, with a sharp ±30 % drop-off in the first six months, followed by a regular decline of nearly 10 % per year.43-45 A much larger decline is evident after PK, however, in which grafts commonly lose upwards of 40–55 % within the first postoperative year. In addition, the rate of decline never appears to stabilize at a lower level, as with DS(A)EK and DMEK.46-48

Complications

Graft

Graft detachment is the most common complication following all forms of endothelial keratoplasty. With DS(A)EK, this may occur in 0–82 % of surgeries.11,49-51 Similarly, detachment rates of 20–60 % have been reported after DMEK, although many of these cases do not appear to be clinically significant.22,35,52-54 Frequently, DMEK detachments are small, peripheral, and temporary. And even when the detached areas are both large and central, some patients nevertheless achieve BCVAs ≥20/40. In our own series, clinically significant detachments—those which reduced the patient’s vision and/or required re-intervention—occurred in 10 % of eyes. Risk factors might include surgical inexperience, failing to completely unfold the donor membrane during surgery, implanting the graft upside down, the use of intra-ocular viscoelastics, use of plastic materials (rather than glass) to inject the tissue into the recipient anterior chamber, insufficient air-bubble support after surgery, and the use of Optisol rather than organ culture medium for graft storage pre-operatively.52-55

Management depends on the size of the detachment. Small detachments (less than one-third of the graft area) resolve spontaneously and rarely, if ever, require re-intervention. Larger detachments, however, have more variable outcomes, complicating the management decision tree. In general, even with large detachments (greater than one-third of the graft area), most corneas eventually clear, although over a longer time period and then only 50 % of patients achieve vision ≥20/40. Because a satisfactory visual result may occur half the time after a large detachment without any subsequent intervention, reoperation – either with re-grafting or re-bubbling – ought to be an individualized decision, tailored to the patient’s preferences (i.e. for more surgery, in light of the possibility of better vision).52-55

Allograft Rejection

Two years after DMEK, the allograft rejection rate is ≤1 %. This is considerably lower than the reported rate after PK (5–15 % in ‘low-risk’ cases), and also lower than after DS(A)EK (10 %).23,37,56-58 Likely, the explanation lies in DMEK’s thinner, stroma-less graft, which may be less immunogenic because it presents fewer antigens to the recipient’s immune system.23,57

Secondary Glaucoma

Because runaway pressures threaten both the survival of the graft and the health of the optic nerve, glaucoma is among the most important potential complications of any form of corneal transplantation. Reported rates after PK and DS(A)EK commonly range from 15–35 %, but sometimes as high as 60 % depending on the patient population and the steroid regimen.59–62 Because the risk of allograft rejection after DMEK is relatively low, a lighter, less intense, steroid schedule is possible. (Specifically, we use 0.1 % topical dexamethasone for just the first postoperative month, then switch to fluoromethalone thereafter.) Perhaps as a consequence, the reported rate of glaucoma is small – just 6.5 % at two years. Most cases arise in eyes with a pre-existing history of pressure trouble, with relatively few “new” cases after surgery.63 Two additional factors may contribute to DMEK’s low rate of secondary glaucoma. First, most patients receiving a DMEK for Fuchs Dystrophy are Caucasian, a population thought to be at lower risk. Second, one week prior to surgery, a peripheral iridotomy is made at the 12 o’clock position to prevent the development of a pupillary block glaucoma.63

DMEK in Phakic Eyes

Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty is safe for phakic eyes, although several additional protective steps are required. Just prior to transplant, the pupil should be constricted with 2 % pilocarpine to protect the lens from accidental damage during surgery, either from air-bubble or instrument induced trauma. Even so, 25 % of phakic eyes may present with mild anterior subcapsular lens opacities or a Vossius ring (iris pigment imprint on the outer lens capsule). Usually, these pigment deposits disappear with time and do not affect final visual acuity. The rate of iatrogenic cataract formation necessitating phacoemulsification is reported at 4% at two years.64,65 As a precaution, the size of the air bubble left behind in the anterior chamber after DMEK surgery ought to be reduced in phakic eyes, from 50% down to 30%. This may help prevent a mechanical angle closure glaucoma from developing (arising when a large air bubble presses against the lens, causing the lens to tilt forward and compress the angle).65

Future Directions

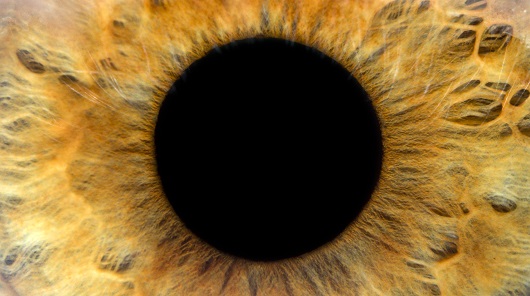

Steadily, reports have been accumulating of corneas with detached grafts (after both DMEK and DS(A)EK) that nevertheless clear.66,67 When these corneas are viewed with specular and confocal microscopy, endothelial cells are clearly visible populating the recipient’s posterior stroma (see Figure 3). The prevailing speculation is that endothelial migration is responsible for this phenomenon, either by the donor cells, or host cells, or both.68-70 If widespread cell migration does indeed occur, then a simplified procedure, tentatively named “free-DMEK” or “Descemet Membrane Endothelial Transfer” (DMET)—in which the donor tissue is merely injected into the recipient anterior chamber after descemetorhexis—could be effective in the management of corneal endothelial disease.71 The advantages of this surgery, even over DMEK, would be enormous: perfect anatomical restoration, complete visual recovery, elimination of virtually all intra- and post-operative complications associated with endothelial keratoplasty, and an enormous reduction in the required surgical skills. Pending further study, DMET has the potential to become the preferred “no-keratoplasty” treatment for corneal endothelial disorders.